Saint Louis Taiji

HunYuan Taiji is system of Taijiquan (Tai Chi Chuan) which unifies a modified version of Chen Style Taiji with Taoist QiGong (Chi Kung) practiced in accord withTraditional Chinese Medical theory and practice. It was developed by GrandMasterFeng Zhiqiang of Beijing, China. The form has been modified so as to make it accessible to all people, young and old, male and female, healthy and challenged. Its immediate benefits are stress reduction, relaxation, enhanced vitalty and the generation of Qi (Chi) for health and self healing. Focus is on movement using correct Taiji (Tai Chi) principles, rather than rigid imitation of superficial choreography. HunYuan Taiji/Qigong has a philosophical component as a form of practical Chinese Philosophy, primarily Taoism (Daoism). HunYuan’s primary focus is on Self Nurturing and Cultivation, with the ultimate attainment being Spiritual Liberation and the Unification of the Individual with Heaven, Earth and the Tao.

Practical Tai Chi Sword

By J. Justin Meehan © June 2006

There is a Chinese Martial Arts saying that “It takes 100 days to master the Broadsword (Dao) but takes 10,000 days to master the Straight Sword (Jian).” For those of us who only practice the Tai Chi Straight Sword form, it could take a lot longer. This is not to say there is no benefit in practicing the Sword form. Practicing the form teaches us balance in use of the sword, helps us to develop a comfortable feel for handling the sword and helps us to concentrate our intention (“Yi”) while extending our energy (“Qi”) through an inanimate metal object.

Unfortunately, besides practicing a number of classical postures, not much of a practical nature in the use of the sword can be learned just by practicing the Taiji Sword form. In order to improve our understanding we may need to learn more about the use of the sword and its differing techniques. The more we understand about sword use, the better our sword form should look.

First of all, it may be helpful to examine the shape and length of the Jian itself. Compared with other types of swords we may be able to see for ourselves what makes the Taiji Sword unique as a weapon. When compared with other swords we can see that the advantage of the straight sword is that it gives us about 3 to 4 feet of distance between ourselves and our opponent. It is obviously more as a thrusting weapon than a curved saber or broadsword, however, it does have a razor cutting edge which is sharpest and most effective in the last 3 or 4 inches toward the tip of the sword.

A thrusting sword such as the straight sword has several vital target areas. The most accessible and deadly are the throat, neck arteries, eyes and into the brain as well from these 3 areas. Additionally, arteries at the solar plexus, underarm and groin would produce a geyser of blood pumping from the heart which could result in total incapacity within 10 to 30 seconds.

Liver, kidney and spleen are also available targets. Because of the 1 1/2 to 2 inch width of the Sword it would be very difficult to attack the heart or lungs directly because of the rib cage. A western fencing foil would have a better chance of slipping between or separating the ribs with a single thrust.

Because of the sharp edge especially toward the tip, cutting, chopping or slicing movements would also be effective against the arteries of the neck and against the tendons, muscles and ligaments of the opponents lead hand and arm assuming it is also extending with sword in hand. Attempting to slice any other part of the body might result in some incapacitation, but not likely to end a deadly duel. Attempting a less serious cut or thrust to any other non lethal target area would also possibly result in exposing one’s own major vital target areas to the opponent. Unlike the game of chess, an uneven exchange of target thrusts could prove fatal for the person attacking a non-lethal target and a thrusting movement is more likely to be quicker more direct and more penetrating than a slicing, chopping or cutting movement.

While it may take 10,000 days to master the sword there is still a lot that can be learned in the first 100 days. Much of what we can understand about the sword can be understood just by using common sense. First of all, let us just pick up and examine the sword. Compared to other weapons its primary benefit appears to be that it provides a 212 – 3 foot extension of a sharp point to our hand. It is ideal for thrusting primarily and also capable of slicing, chopping and cutting. If we found ourselves in need of a weapon and this was the weapon at hand it would be useful to keep an opponent at a distance of about 4 or 5 feet depending upon how far we held it in front of our body. The greater the extension the greater the reach and the greater the protective distance between ourselves and our opponent.

Using the reach keeps the opponent somewhat at a distance, depending upon what if any weapon he possessed. But extending the arm too straight sacrifices the use of the body of the sword to block, parry or deflect. As a result, keeping the sword in front of our body and pointed toward our opponent at all times, enables us to take advantage of the shortest distance between two points (our sword tip and its target area). Keeping the arm somewhat bent allows us to protect and defend against the thrust of our opponent.

And we see just such a basic “on guard” posture utilized in most types of European fencing and Olympic sports fencing. The sword is held in front of the body, between the lead sword hand and the opponent, with the tip always facing the opponent. It is very unlikely in Western fencing to find “on guard” sword postures where the sword is held behind the body or in such a way as to not point directly at the opponent. And yet in many Taiji and Chinese Martial Arts sword forms we find just such unpractical sword postures, such as “Archer Shoots the Geese” or “Big Star- Standing on One Leg” and “Little Star- Standing on One Leg.” It’s not that these postures are of no real usage, it’s just that they are sacrificing the protective distance that an extended sword offers and removing the effective portion of the blade tip from the vital target areas it should be trying to reach. As a result, while beautiful in appearance, it could prove disastrous or needlessly risky in application. In all fairness, Japanese fencing also uses “on Guard” stances where the sword is held above or behind the body, but it must be understood that the Japanese sword is also a curved bladed weapon primarily used for cutting.

The statement that it would take 10,000 days (almost 27 years) of study, also meant that in all likelihood the sword would only be mastered by someone with the sufficient leisure time for practice and financial ability to pay or other opportunity for instructions. As a result, the sword is often associated with either professional soldiers of higher rank (most common foot soldiers carried either the broadsword or spear), marital artists or aristocrats. Even here though we have to distinguish between the ceremonial and ornamental sword worn by certain scholars and officials with the battle sword, which was heavier, studier and seldom flexible.

Naturally, the battle sword had to be stronger, because it often had to penetrate and cut against arms, armor and other protective coating. The sword available to aristocrats in more urban environments, just as in the fair City of Verona where Romeo and Juliette took place, was often worn as a fashion accessory and symbol of status. To be used in an urban environment the sword would only need to cut through cotton and silk vestments and clothing. As a result having a higher spring steel content allowed a blade to be lighter, more flexible and carry a sharper edge.

But we must differentiate between the types of fighting swords used in the past with actual fighting utility and many of the useless flexible swords used in the recent past and present for Chinese Wu Shu Jian forms competition. Fortunately, now in many competitions rules prohibit sword forms competitors from using a sword that is so thin and flexible that it will not support its own weight when balanced point down on its tip. Futhermore, new international rules standardize competition swords and require greater realistic quality. Most tai chi swords today are in no way representative of the quality and workmanship of classical straight swords of China. Even sturdier but flexible Dragon Well swords pose a practical problem. If a thrust is not completely straight the sword blade may bend instead of allowing the point to penetrate.

The straight thrust uses almost exactly the same posture in both Western fencing and Chinese straight sword usage. A good way to test the usefulness of a practice blade and the straightness of the thrust is to practice against a watermelon. This practice is only advisable for mass market swords as the moisture will cause rust in realistic “high carbon” swords. If the blade is too flexible or the thrust is not straight the sword will bend and not penetrate. Other techniques can also be practiced using the watermelon as a training device. Cut the watermelon in half and, after enjoying the melon first, use the exposed edges of the hollow half for practicing chopping and pointing (using a downward flick of the wrist to cut down, using the point and point edge against the opponent’s sword hand, thumb and wrist).

There are also many 2 person routines that can be practiced together by two partners using wooden swords that allow for practice of cutting, pointing, chopping, thrusting and other sword techniques. In some international Wu Shu competition, a sword form competitor will not be given a score unless he/she can demonstrate practical usage of at least 7 basic sword techniques. This could result in disqualification of many of today’s Taiji sword form competitors who primarily demonstrate continuous, circular sword movement without well defined basic sword techniques.

Some masters list as many as 30 different sword techniques. Naturally, the most common and important to master include:

- thrusting or stabbing,

- slicing,

- chopping,

- cutting,

- pointing and picking;

- parying,

- blocking,

- beating,

- intercepting,

- whipping,

- lifting,

- pressing,

- sliding,

- following,

- wrapping, and

- drawing

Each one of these techniques must be mastered correctly, practiced regularly and tested with a partner or opponent under even more realistic but safe conditions.

Some may argue that Taiji Sword does not need all these techniques because of its “sticking sword” practices and exercises. The most often cited example is the old footage of Cheng Man Ching practicing sticking sword with his students. What many people fail to realize is that this was an exercise where only one person is active and the other person only attempts to stick and neutralize. Then the partners exchange roles. It was not a contest between two persons fencing each other. There are also numerous 2 person drills which in some way are similar to push hands practice. Although similar they do not necessarily prepare one for fencing. Only fencing prepares for fencing.

Today’s Chinese Wu Shu tournaments often feature fencing competitions with padded weapons. The padding alone often changes the weight and effective use of the sword. We are probably still a long way off before electronic equipment and protective clothing will allow competitors to fence with electronic scoring, just as in Olympic fencing. Fencing competition results in the immediate elimination of many extravagant postures and techniques. There is much that students interested in Chinese fencing can learn from Western fencing practice and theory.

This is not to say that practicing sword form alone is of no benefit in understanding sword usage and taiji principles. Sword form helps us to develop a “feel” for the sword and the movements which compliment the sword’s shape and weight. There are important differences, however, between Taijiquan empty hand theory and practical Taijijian sword usage. For instance the Taiji Classics state that “the waist leads the movement” and that “the root is in the foot, develops in the legs, is controlled by the waist” and only then does it function in the hand and fingers. While this maybe true of Taijiquan, it is not always true with sword. Closer in theory to the Bruce Lee lunging lead hand punch, which he derived from western fencing practice, the lead hand moves first. In fencing speed, timing and accuracy are more important that power. The sword blade will do the rest.

Suggested Resources

These are not the only sword masters but they are outstanding teachers in Chinese straight sword who have been recognized by all as to their high level ability and who have produced outstanding sword students as well:

- He Wei Qi — Long Island, N.Y.

- Liang Shou Yu — Brit. Columbia, Canada

- Yang Jwing Ming – Mass

- Nick Gracenin – PA

- Grace Wu-Monnat (daughter of Madam Wang Ju-Rong) – KS

- Sam Mascich — Vancouver, Canada

- George Xu — CA

- Scott Rodell – Washington, D.C.

- Wu Wen-Ching, Rhode Island (R.I.)

Suggested Books and Videotapes

- Sword Imperatives, a book by Wang Ju-Rong & Wu Wen-Ching

- Taiji Sword, Classical Yang Style, a book by Yang Jwing-Ming V7

- The Art and Science of Fencing, a book on European Fencing by Nick Evangelista

- Secret History of the Sword, book on European Sword History by J. Christoph Amberger

- Chinese Swordsmanship: the Yang family Taiji Jian tradition, a book by Scott Rodell

- Othodox Chinese Taiji Sword, a video 32 Standard Taiji Sword Routine and techniques by Wang Ju-Rong

- Five Section Tainian Two Person Sword Form, a video by Sam Masich

2001 Grand Master Feng Lecture

Like the Body of a Dragon

Notes from the 2001 Feng Zhiqiang San Francisco Intensive

edited by Malcolm Dean

translated by Brian Guan

In July 2001, Grandmaster Feng Zhiqiang, the founder of Hunyuan Taiji, gave a four-day intensive near San Francisco where he presented several wide-ranging lectures on principles of taiji practice and philosophy. Here are a few of his comments on principles of practice. Where Master Feng is quoted, the translation is from the audio tape of his lecture; otherwise the material is condensed from the audio or from our notes. We’ll try to bring you some of his very interesting comments on taiji philosophy later on. Many thanks to Brian Guan for his translation. — ed.

Six Principles of Hunyuan Tai Chi Practice

During his introductory remarks, Grandmaster Feng discussed six basic principles of Tai Chi practice. They were:

- Gentle is better than forceful.

- Slow is better than fast

- High is better than low.

- Long is better than short.

- Curved is better than straight.

- Single-weighted is better than double-weighted.

Comments on the Principles

1. Gentle is better than forceful.

Hunyuan taiji, like Chen style taiji in general, is an internal martial art. But it’s all too easy for students to succumb to the temptation to use stiff external force. In terms of practice, “forceful” means over-exertion: stiffness of body, rigidity of intention and sometimes even a showy, martial performance style. In other words, too much yang, not enough yin.

For this reason, during the intensive Feng Laoshi (teacher) recommended the elimination of any excessive or showy fajin during practice. [ Fajin is the explosive release of energy at critical points in the practice forms where martial techniques would be applied if in actual combat.] Fajin is a traditional part of taiji, but it’s dangerous if not done correctly, ha said. If the energy is not released cleanly, the chi can bounce back into the body and cause tissue damage. Some taiji players exaggerate fajin and end up injuring themselves. Feng Laoshi made clear he considered such exaggerated exhibitions to be both counter-productive to the development of gongfu (internal strength and ability) and an example of poor form.

In his own demonstrations, Master Feng refrained from any stamping fajin , and only occasionally issued power through the fist or elbow, and then only with moderation. In his remarks, Grandmaster Feng emphasized that this is because fajin , even if it is done correctly by an experienced player, can cause harm to the body over time by damaging the tissues, especially the joints, internal organs and brain. Stamping can cause long-term harm to the knee and hip joints, as well as the internal organs, and punching can actually cause a concussion-like effect on the brain. He cautioned that the damage may not show up immediately, but may manifest later in life and cause health problems. So gentle is better than forceful.

2. Slow is better than fast.

Just as being too forceful in practice is detrimental to the development ofgongfu , so is being too fast. The development of true internal strength and skill requires two things: internal self-knowledge and internal relaxation. Internal self-knowledge can only be gained by experience. The student must practice slowly and gently enough to see and understand every nuance of his or her movement, from the top of the head to the tip of the toe and out to the ends of the fingers. That’s why slow is better than fast. Internal development also requires internal relaxation, which means both mind and body must be calm and open. Just as too much force in the body results in stiff movement, too much force in the mind results in stiff intention. Both damage the flow of chi and must be avoided. Therefore, again, gentle is better than forceful. Gentle does not mean lax, however; it means alert, awake, aware, yielding, returning. Therefore slow and gentle is better than fast and forceful.

3. High is better than low

Master Feng emphasized that constant practice in a stance that is too low can cause long-term damage to the body, especially the knee joints. [Again, Master Feng was commenting on poor habits developed by some over-enthusiastic younger practitioners, who push themselves into very low practice stances in order to build strength and martial ability as quickly as possible.]

Feng Laoshi also pointed out that there can also be an interruption of chi flow in low stances that compromise a move’s effectiveness in martial application. A stance that’s too low will cut the flow of chi at the knees, and will also cause leakage through the huiyin (perineum). Grandmaster Feng stated, “…when you have very low stance, chi leaks out from the perineum. There’s no way you would know. When chi leaks out from the perineum you can never sense it. Also, when >you have very low stance the angle at the knee is too sharp, so chi can’t flow down the leg very easily. We must differentiate between what is good for us and what is bad for us, and what is damaging our body and what is nurturing our body… When you are practicing in lower stance, yes, your martial ability may increase faster, but you’re doing damage to your own body, and you don’t even realize that you’re leaking chi.” So high is better than low.

4. Long is better than short

One of the most important principles of Hunyuan taiji is learning to relax the joints and fully extend the arms, legs and spine.

This promotes the flow of chi and creates a body “like a dragon”. Grandmaster Feng explained, “…Taiji is a ‘long’ form of martial art, as in stretching, lengthening. Xingyi [another internal martial art related to taiji], in contrast, is a shorter form, more compact. Even though Xingyi is a short form of martial art, it uses the body’s natural springy, jumpy power to make up for the lack of reach. However, taiji is a long form of martial art. It’s like the body of a dragon. Tongbei, another Chinese martial art, is another long form of martial art, because you are always extending your arms. Taiji absorbs the strength of all these different martial arts and forms its own unique style. This movement in our form [he demonstrated a move] is from xingyi. This [he demonstrated another move] is from tongbei. This move is from Shaolin. This is from Preying Mantis. This is also from Preying Mantis. The elbow strikes in taiji come from Baji. Taiji is a compound of eighteen other martial art styles. [Taiji uses] the theory of Taoism, the I Ching [Book of Changes], and Chinese Traditional Medicine to form its theoretical foundation, especially yin-yang theory and the meridians in traditional medicine.”

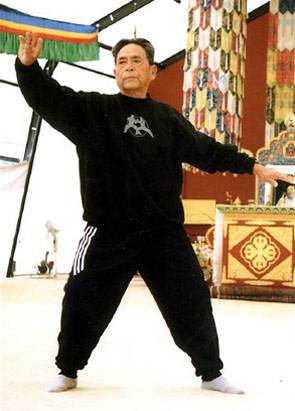

In performance, Master Feng himself expressed very long, large movements, fully extending his arms (see photo above) by gently opening and releasing the joints. Since he has an enormous reach, the effect is heightened, but his arms are never over- or hyper-extended. They always retained a natural, relaxed curve. Even though in application movements may be very small and concise, in practice they should be large, round and long to better promote the flow of chi and build gongfu. Thus long is better than short.

5. Curved is better than straight.

Grandmaster Feng stated: “But even when your limbs are lengthened, they’re also curved. The body is the same. It should never be too straight. There should always be a curve. In taiji the body is considered to have five bows, as in “bow and arrow”. So one arm, the other arm—two bows. One leg, the other leg and your spine, three more. So, five bows. There is a taiji saying that your body has five bows, and if you can express the springy power [in these five bows] there is no opponent under Heaven [who can beat you]… Curving the chest is also a bow [this is the obverse to curving the back]. Only by practicing in a slow and lengthening manner, can you then cultivate this springy energy. Something with springiness is very strong. If you drop it, it won’t break. But if you have something that is hard and brittle, when you drop it, it will shatter. That’s what the old martial arts masters would say: If your body has five bows and you can do the spring-like energy, you will have no enemy and no opponent under Heaven [who can beat you]. Practicing martial arts, you should know the theory. Only by knowing the theory can you grasp the martial art aspect.” So curved is better than straight.

6. Single-weighted is better than double-weighted.

Double-weighted” means the weight of the body is evenly distributed on both feet. ” Single-weighted ” means the weight is on one foot. Double-weighted is bad because it’s static; when both feet are grounded, it’s hard to move or turn. Single-weighted is good because it’s dynamic; it’s easy to move when one foot is grounded and the other free. In push-hands, “double-weighted” also implies using force against your opponent’s force, while “single-weighted” means yielding to force first in order to neutralize it, then applying force into emptiness – in other words, using “four ounces to move one thousand pounds”.

Grandmaster Feng explained: “Weight on one side is better than evenly distributed. Single-weighted is better than double-weighted. Even when you are standing upright, your weight should only be on one leg. When you’re standing you should be relaxed and have your weight shifting from one leg to the other, never fifty-fifty. But don’t be too obvious. That looks funny. Don’t let it be visible to an observer, but [even when standing] you should shift your weight from one leg to the other. Same thing with the foot. When you are standing you should never tighten your foot, and you should instead flex it gently. Never stay in one position.”

Master Feng never stopped this kind of subtle practice for the entire four days of the intensive, even when he was lecturing or resting. It seemed so natural that it was not noticeable, but if you looked closely, you could see he was always gently moving. Even when he was apparently standing still, he was actually gently rocking his weight back and forth from foot to foot, as if performing a slow-motion qigong.

Grandmaster Feng Zhiqiang in “Leisurely Tie Coat” from the Hunyuan 24-movement first form. At Pema Osel Ling, near Santa Cruz, July, 2001.

Philosophical Foundations of the Chinese Garden Aesthetic

The following is an excerpt from the lecture of J. Justin Meehan, Esq. delivered at the past CFG Appreciation Tour

There is a very special aesthetic to the Chinese Friendship Garden (CFG) and to Chinese Gardens in general. which gives them a uniqueness differing from European and even Japanese Gardens. This aesthetic is based on a Naturalness in both appearance and design. By comparison, European Gardens were characterized by symmetrical and artificial arrangements which demonstrated their belief in the triumph of human reason over Nature. This is easily seen in the geometrical arrangements in the Gardens of Versailles in France. In fact, reports of Chinese Gardens by missionaries and other travelers in the 1700s had a profound impact in reshaping European ideas for Gardens.

Its not that the Chinese did not also attempt to impose reason and order in design and architecture, however they did so primarily in regard to human living environments rather than natural or garden type settings. The Forbidden City in Beijing is almost completely= designed using lines and angles not found in the natural environment. Lines and angles were necessary in order to create living spaces which took into account differences in relationships and social status between classes of peoples, even between family members. These relationships were an essential part of the Confucian philosophy designed to create the ideal balance of social responsibilities and obligations for a well ordered society. For the most part, these relationships were unequal (eg. subject and ruler, father and child, husband and wife, older brother and younger) requiring differing accommodations both in terms of behavior and space. This authoritarian and hierarchical designation of living spaces put each person in his proper place.

Counterbalancing the Confucian ethic, was the Taoist philosophy. Both appeared at about the same time (between 555 and 300 BCE.) and can be seen as having a relation to each other similar to the Taiji (yin/yang) diagram, with Confucianism forming the Yang (male, authoritarian) division in relation with Taoist philosophy forming the Yin (feminine, natural) side of the paradign. Though outwardly different, they co existed side by side within Chinese Society and the Chinese Personality. It has been said that the Chinese Gentleman is Confucian in his public life and Taoist in retirement. They also co exist in the Chinese £rarden itself. A typical Scholars Garden would have 4 major elements: plants, rock, water and human bufidhigs plating man squarely within the natural environment, not,above it and certainty in n balance and not opposition with nature.

Taoist philosophy is a belief system that points to an Unidentified Origin of all things which is beyond human comprehension or even the ability to describe in words and therefore is assigned the word Tao or Way. From the Tao emerged all things and is Tao’s influence is ever present in terms of the Way things are. In looking for the Tao we cannot find it, but its operations are most clearly understood in terms of Nature and the way things are naturally. Contrary to Confucian philosophy, the Taoist is seldom a group conformist, but is found rather abandoning convention in order to follow the Tao. While the original Taoists who had abandoned public life for a life of seclusion in Nature, philosophical Taoism infused and inspired Chinese life in many ways, especially in the arts (painting, poetry, calligraphy, architecture, design and even the martial arts) and even fostered a quasi scientific approach to explore medical treatment, the use of herbs and acupuncture. The essence of the Taoist approach was to accept things the way that they are, go with the flow and avoid making things worse by trying too hard to make things the way we want them to be, which often results in creating the exact opposite of what we originally intended. Appreciating the natural and spontaneous is at the essence of the Taoist aesthetic of Chinese Gardens.

Of course there all kinds of other considerations to be taken into account. There are different types of Chinese Gardens such as the Imperial Gardens created for Emperors and their Court. There are Temple Gardens built around Taoist and Buddhist Temples. There were the private gardens built by wealthy families to display their wealth and status and most often used like beach houses in the Hamptons (or the Lake) for conspicuous entertaining. And, of course, there was the Scholar’s Garden built for withdrawal from the rat race of society and allowing for rest, seclusion, reflection, study and self cultivation, or at least the appearance thereof Gardens also differed depending on their geographic location and the era in which they were built. Most Gardens existent in China today were for the most part built quite recently, within the past 200 years or less. While modem study of Chinese Gardens tends to focus more on socio-economic factors, it is the Chinese Gardens ability to reveal and reflect traditional Chinese culture and values that interests me the most.

Although Chinese Gardens are an intentional attempt to recreate the naturalness, balance and spontaneity of Nature within prescribed confines, Chinese Gardens seem much less contrived or improved upon than Japanese Gardens which seem so perfectly arranged. Perhaps limited by the island of Japan’s lack of space or proscribed by the essentialism of Zen (Chan) Buddhist philosophy, a Japanese Garden can seem so perfect as to make one’s own entrance seem somewhat of an intrusion. It has been said that where Zen seeks perfection, Taoism seeks balance. The perfection of the Zen Garden often reminds us of just how confused our own lives and mind seem in comparison.

Chinese Gardens on the other hand invite the guest to enter and enjoy. Various pavilions, whether for study, play or show, place the human being within the center of the natural environment, not above or below. Chinese Gardens call out for every type of artistic participation and social response. Music, poetry, painting, dance, calligraphy, word games and drinking all fit well within the way things are in the Chinese Garden. No Garden would be complete without written calligraphy, colorful painting and other evidence of human artistic appreciation and interaction. All Gardens, whether European, Japanese or Chinese reflect each culture’s philosophic understanding and invite artistic response. Each Garden is in effect a vital cultural museum.

Another aspect of Chinese Gardens that I enjoy can be experienced in the Nanjing Friendship Garden of St. Louis. This garden was created only after a Feng Shui Master personally examined and approved the layout, positioning and design. As I have been teaching Taijiquan and Qigon in the Missouri Botanical Gardens over the last 15 years or so, myself and my students could not help but experience the harmonious yet abundant balance of energies in the Chinese Friendship Garden. This is what led me to fall in love with the Garden and to want to further explore and learn more about the Garden design. It is a perfectly balanced environment and full of vital energy or Qi (chi). Stepping into the Garden is like stepping into another time a place where one can leave one’s troubles outside and experience the peaceful calm and balance within and be restored and revitalized by the resevoir of “qi” within.

Having just returned from China this year after my first visit in 1981, some 25 years ago, it is obvious that traditional culture is being steamrolled by the global culture of consumerism and materialism. To the extent that cement boxes, buildings and department stores and Golden Arches are crowding out and replacing thousands of years of civilization, Chinese Gardens stand like spiritual stop signs to modem progress reminding us of the values and treasures of traditional Chinese Culture. Just as the 3 Georges Dam flooded out and destroyed centuries of civilization in sacrifice to modernization, the benefits come with a cost and loss. Traditional Art and Culture built up over thousands of generations gives way to instant gratification and multinational corporate culture. Shall we allow the gifts of our ancestors to be lost to our children, or can we protect and preserve the cultural legacy of oldest living culture for our posterity and the posterity of the world, before it becomes all too late?

Our Chinese Friendship Garden is the most visible architectural symbol of traditional Chinese Culture in St. Louis today. But the Chinese Friendship Garden is made of wood, mortar, plaster and stone, some found only in Nanjing. These elements deteriorate over time. The CFG needs repainting every few years. Some of the Pavilion wood is getting old and needs replacement. Mortar from “cracked ice” walkways comes loose as visitors come and go. Tiles break and colors fade. The CFG needs regular maintenance, repair and upkeep. There are also plans for a Dragon sculpture to bring visitors attention to the entryway, so that they do not miss the opportunity to enjoy one of St. Louis best kept cultural secrets on their way to the more well known and visible Japanese Garden. The Mo. Botanical Gardens does not have sufficient adequate financial resources to preserve and protect the CFG. Its resources are stretched thin and attention must be allotted over several differing projects and areas in the Mo. Bot. Garden.

In order to assist the MBG to better care for and maintain the CFG a group of concerned citizens have formed a not for profit organization called the Friends of the Chinese Garden in order to help raise awareness of and support for the CFG. They will plan fund raisers and cultural events to better assist the MBG in popularizing the CFG and it helping with upkeep and development. They are already working on creating a documentary on the CFG to share with the MBG and other educational organizations on the history and cultural importance of the CFG. They are also working on a Mandarin House Restaurant fund raising dinner scheduled for next Fall and Spring. A newsletter for members is al being planned. Anyone with time and interest is invited to become part of the Friends of the Chinese Friendship Garden organization. A special account has been set up by the MBG for the CFG which allows interested persons and organizations to donate directly to a fund whose use shall be ONLY for the needs of the CFG.

Interested persons can find out more by contacting FCC President, J. Justin Meehan at jjustinmeehan@ao.com Donations to the CFG can be made directly through the MBG with checks made out to the

MBG c/o Chinese Friendship Garden Fund

P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, Mo., 63166

Friends Return to Honor Chinese Friendship Garden

Another successful Margaret Grigg Nanjing Chinese Friendship Garden Tour and Celebration was held this past Sunday, April 29, 2007 at the Mo. Botanical Garden (MBG) as part of its educational offerings and adult education program. The class registration was overflowing and has a long waiting list for the next offering. For the second time in a row, the weather was wonderful!. Participants were treated to an hour of interesting lectures by Chinese Friendship Garden (CFG) presenters including MBG Taiji/Qigong Instructor Shirfu/Sifu J. Justin Meehan who is the organizer of this class, assisted by Jackie Mitchell who conducts Garden tours for the MBG. Sifu Justin, who is also President of the Taoist Research and Resource Forum of St. Louis, lectured on the Taoist origins of Chinese Gardens and the problems facing the CFG today. Jackie Mitrchell presented a slide show comparing the CFG with other Chinese Gardens in China today. Also presenting was Douglas Wagganer, a construction supervisor who shared original drawings and his knowledge of CFG.

After the lecture portion of the program, participants strolled out to the CFG to tour the Garden and enjoy the CFG experience. There waiting for them were Ms. Li Zhi Lu a Chinese student studying at Webster University who played the Chinese stringed instrument known as the Guzheng creating a musical environment transporting visitors back to another time and place in Chinas past. Alongside the musical atmosphere, Madam Goretti Lim created a moving masterpiece of Chinese Hun Yuan Taiji and Qigong. Madam Lim is also getting ready to compete in an upcoming National Taijiquan Competition to be held this July in Houston, Texas where she will compete and demonstrate her mastery in Taiji form and Sword. Sifu Justin led participants in drawing energy from the natural environment in a series of Hun Yuan Qigong (chi gong) exercises designed to reduce stress and enhance vitality. Serving tea to participants were Donald Lee and other leading members of the Fo Guang Shan Buddhist Temple who practice the Humanistic Buddhism of Yen. Master Hsing Yun whose expression of enlightened Buddhism emphasizes joyful engagement with the community at large and service to others.

Ms. Mimi Huang of Taiwan Marcoview TV recorded the event for the purpose of creating a video documentary of the CFG which will be made available to the MBG, public television and local educational institutions upon completion. Also present reporting the event were Editors Francis Yueh and May Wu of the St. Louis Chinese American News whose support of the CFG and assistence in providing volunteers and artists made the entire event possible. Their crusading advocacy on behalf of the CFG last year (see www.SCANews.com, Nov. 2, 1966) led to needed repairs on crumbling stone masonry by the MBG and the coming together of concerned citizens who later formed the Friends of the Chinese Garden, which is now being incorporated as a Not For Profit corporation thanks to the volunteer legal services of local attorney, Ms Yi Sun, a graduate of Washington University Law School, originally from Shandong Province, China, who also serves as Friends of Chinese Garden liaison with the St. Louis-Nanjing Sister City Program. To these volunteers and contributors we owe a great deal of gratitude for taking the time and showing the interest in preserving Chinese Culture in their support of the CFG.

Resources

Books & Media

Listen to the Fragrance

The Portland Classical Chinese Garden, Lan Su Yuan, grew out of a friendship between the sister cities of Portland, Oregon and Suzhou, a Chinese city renowned for its ancient gardens. Lan Su Yuan – poetically named the Garden of Awakening Orchids – is a microcosm of nature’s splendors contained in an urban setting. Created to nurture and inspire all who visit, this classical garden is little changed from what might have greeted visitors during China’s Ming dynasty.In Chinese tradition, garden landscape without poetry is not complete, and Lan Su Yuan is graced with a wealth of poetic inscriptions. In Listen to the Fragrance, Professor Charles Wu provides translation and insightful commentary, guiding us on a literary tour of the garden and revealing hidden meaning among its flowers, moving water, Lake Tai rocks, and elegant architecture. With stories and legends from ancient dynasties and images of scenic wonders from China’s vast history, the inscriptions deepen our appreciation of Lan Su Yuan’s beauty. The rich canon of classical Chinese poetry enhances the garden as a new setting for China’s enduring culture.

Listen to the Fragrance will engage readers in the poetic conversation deeply embedded within the landscape of classical Chinese gardens.

Gardens in China by Peter Valder

With their distinctive characteristics, the gardens of China are among the most fascinating in the world. Many excellent books have been written about them but, on the whole, they have dealt only with the surviving imperial gardens and a selection of those of retired officials. Rarely are the fascinating courtyards and gardens of temples mentioned, nor the evocative enclosures of ancient burial grounds and imperial tombs – to say nothing of the public parks, botanical gardens and arboreta, most of which have sprung up since 1949.

In this book Peter Valder describes over 200 gardens in China which he has visited, including representatives of all types. In order to introduce them, he looks at how over the years Western visitors have perceived and come to understand Chinese gardens, and for each site provides notes on its location, history and plants. A description of more than 200 imperial, private, temple, botanical and public gardens in China, including notes on their history and significance, together with 500 color photographs.

$49.95 and

The Chinese Garden

History, Art and Architecture

Third Edition Maggie Keswick Revised by Alison HardieDense with winding paths, dominated by huge rock piles and buildings squeezed into small spaces, the characteristic Chinese garden is, for many foreigners, so unlike anything else as to be incomprehensible. Only on closer acquaintance does it offer up its mysteries; and such is the achievement of Maggie Keswick’s celebrated classic that it affords us–adventurers, armchair travelers, and garden buffs alike–the intimate pleasures of the Chinese garden.

In these richly illustrated pages, Chinese gardens unfold as cosmic diagrams, revealing a profound and ancient view of the world and of humanity’s place in it. First sensuous impressions give way to more cerebral delights, and forms conjure unending, increasingly esoteric and mystical layers of meaning for the initiate. Keswick conducts us through the art and architecture, the principles and techniques of Chinese gardens, showing us their long history as the background for a civilization–the settings for China’s great poets and painters, the scenes of ribald parties and peaceful contemplation, political intrigues and family festivals.

Updated and expanded in this third edition, with an introduction by Alison Hardie, many new illustrations, and an updated list of gardens in China a ccessible to visitors, Keswick’s engaging work remains unparalleled as an introduction to the Chinese garden.

A Master Feng Zhiqiang Early Lecture on Taijiquan & Body Mechanics

Taijiquan is an Art form which is all embracing. It is the union of Yin and Yang. Yin refers to both the Earth and the Moon and Yang refers to both Heaven and the Sun. According to traditional Chinese philosophy, Taiji is the origin of all that exists in the universe. Taijiquan was created based upon the philosophical theory of Taiji.

Taijiquan is an advanced martial art which increases the practitioner’s health through a combination of breathing exercises and internal energy practices or QiGong. Taijiquan Shadow Boxing is not only a superior fighting method but also promotes good health and longevity. For these reasons, Taijiquan is respected throughout the world. It is also becoming popular as a competitive sport in many countries outside of China.

Chen style Taijiquan is an ancient form of martial arts with a history of several hundred years. It is characterized by its spiral like twisting and turning of the body while simultaneously extending and contracting the limbs. A Taijiquan practitioner can strike with any part of his body which has come into contact with his opponent. Furthermore, once a Taijiquan practitioner begins to move he is on the path of a circle. We can say that every movement is a Taiji circle.

In following the Taijiquan path, we must combine study, practice and usage or applications into one. To practice well one must understand Taijiquan theory. Without a real understanding of Taijiquan theory, one cannot practice well.

Another aspect of Taijiquan practice is that it is so relaxing. Performing Taijiquan is like “swimming in air”. The circular movements feel as if we are painting a beautiful picture in the air, tracing the circularity of the Taiji diagram. Practicing Taijiquan also has the purpose of promoting the flow of one’s Internal Qi (vital energy). It assists in making the Internal Qi flow throughout the entire body. In order to accomplish this one must practice in such a manner as to be fully relaxed. The body posture must be upright with the back straightened and aligned. The movements must be light and sensitive without the use of stiff force. The crotch must be opened and the hips rounded. The movements, whether extending or curving, opening or closing, must all be natural and the forces of Yin and Yang kept in unified balance.

There are some practitioners of Taijiquan who have practiced for many years yet still complain that they are unable to feel that their own Internal Qi has started to flow or even do not know what the Internal Qi actually is. They have expressed their hopes that the Master could give them some advice so that they could better understand.

WUJI/STANDING

My understanding is that Taiji (the Great Ultimate or Unity of Yin and Yang) comes from Wuji. Wuji refers to a State of Nothingness or Empty Space, the Void. This indicates that one must practice Wuji standing first. Wuji standing is done by standing with feet shoulder width apart and weight equally distributed on both feet. The arms hang down naturally and the mind is in a state of quiescence.

Through the practice of Wuji standing the Internal Qi will be cultivated within the body. Vitality will be strengthened. Wuji standing will produce and combine the Yin and Yang energies. At the same time, Wuji standing allows the turbid Yin energy to descend downwards and the pure Yang energy to ascend upwards. Consequently, the Internal Qi in one’s 5 internal organs (kidneys, liver, spleen, heart and lungs) will be strengthened and the Internal Qi will flow smoothly through the Qi meridians and channels. This will achieve the result of the combination of internal and external until the whole body is filled with Internal Qi.

Wuji, the state of nothingness, gives birth to Taiji, the union of opposites. Taiji gives birth to Yin and Yang. The Yin and Yang gives birth to the Three Geniuses. The Three Geniuses give birth to the Four Symbols. The Four Symbols give birth to the Five Directions. The Five Directions give birth to the Six Combinations. The Six Combinations give birth to the Seven Stars (Big Dipper). The Seven Stars give birth to the Eight Diagrams. The Eight Diagrams give birth to the Nine Squares. And the Nine Squares return to Taiji. After this we return to Wuji, the State of Nothingness. We both start with Wuji and end with Wuji. Hopefully, Taijiquan enthusiasts will someday be able to experience this as a result of their own practice.

PRINCIPLES OF CHEN 48 TAIJI POSTURES/MOVEMENTS

In response to the requests of many martial arts circles, the 48 posture Chen Style Taijiquan was completed in 1983 based upon the first routine (I-Lu) of the original Chen Style Taijiquan. The 48 form contains all the original postures of the old set while eliminating the many repetitions of postures (and adding some additional postures).

Chen Style Taijiquan has its own characteristics and requirements. Movements are characterized by: spiral twisting and turning; fullness and roundness of the Internal Qi; the coordinated rotation of the 18 body parts (i.e. 2 shoulders, 2 elbows, 2 wrists, 2 hips, 2 knees, 2 ankles, 2 buttocks, the chest, the waist, the abdomen and the neck). It is through constant practice of the spiral twists and turns of each of the 18 body parts that we achieve the rotation of the body as a whole and the formation of the “Taiji Ball” inflated by the Internal Qi within the whole body. This is our goal.

The characteristics and requirements of the 48 Posture Chen Taijiquan are as follows: Once one part of the body moves, the rest of the body must also move together in coordinated manner. Each movement is a part of the Taiji circle. Everywhere there are spiral twists and turns as well as contracting, bending or extending. And everywhere there is a clear differentiation betweea Yin and Yang.

Any part of the body may be utilized to strike the opponent. The hand, elbow and/or shoulder can be use to strike. So too the head, chest and hip can strike. Every part of the body may be used to strike. In addition, once one is in contact with one’s opponent, any part of the body can be used to neutralize an attack by our opponent. Stick to your opponent wherever you may have engaged at the point of contact. Use spirals and twists.

Another characteristic is that opening and closing is like carefully drawing a strand of silk or thread. Changing our posture is like twisting and spiraling. Through practice of the Chen Style Taijiquan we can achieve the end result of integrating various body parts into a unified whole and creating a round ball inflated with the Internal Qi within the body.

Therefore, when practicing Taijiquan we must avoid the use of clumsy (stiff or brute) force. Be sure to use the body as a whole. Be sure to combine both the external and internal. Be sure to keep the body posture upright and avoid leaning. The head must be kept centered and upright “as if suspended from above.” The crotch must be rounded and opened.

The crotch must be rounded and in the shape of the arch in a bridge. If the crotch is pointed (like a pyramid or triangle) it will be without force to the sides and the legs will have no outward strength or lateral support. If the crotch is flattened horizontally like a flat or square bridge, it will have no upward force in the center. So the crotch must be in shape of an arch. It is referred to as crotch opening and hips rounding. There must also be the hollowing of the chest and the substantiating of the abdomen.

The whole body must have 5 bows (2 arms, the back and 2 legs). Each part of the body must be slightly bent, or bowed, or arched. The chest must be tucked in and the back rounded. The arm must be curved and the wrist slightly bent. When you extend your arm outward, drop your shoulder and sink your elbow. As a result, your arm will be curved or bowed. Once you relax your palm, you have an arch. Also, when you bend both legs, you also have an arch. When anything becomes too stiff and straight it is sure to be broken.

When practicing we should pay attention to using the mind, and not the Internal Qi to direct our movements. If your focus is on the Internal Qi it will be sluggish; if you practice with the mind; it will flow. When practicing with the Internal Qi do not use force; if you use force it will break. Our forefathers said: “Practicing Taijiquan is like swimming in Air.” It all depends upon the mind and not on the use of clumsy, stiff or brute force.

The most striking point of this style is the very existence of empty and full; the Yin and the Yang; and the hardness and softness in opening and closing movements. When demonstrating the form there is the lengthening and shortening; the bending and stretching; the contracting and expanding. We should encounter the secret of opening and closing throughout.

There are circles throughout our practice. They can be categorized as clockwise (shun) and counter—clockwise (Nee) when the elbow and palm rotate outward we have “Nee”. When the elbow and little finger of the palm rotate inward we have “Shun”. Shun denotes sinking, closing, relaxing, soft or the Yin aspect of arm rotation. Nee denotes’ the opening, expending, rotating outward, hard or Yang aspect of arm rotation. The same can also be said of the legs. (Keep in mind that relaxing is not the same as collapsing or emptying. In Yin there also is Yang and vica versa).

Once we encircle clockwise or “Shun” the Internal Qi and blood returns to the center. And when we circle counter clockwise or “Nee” the Internal Qi and blood will flow outward to the extremities. To encircle our opponent, “Shun” first then “Ni”. First entwine with softness and then later send out power (as in “store first and then release”), this uniting soft and hard, Yin and Yang.

8 ENERGIES/METHODS

When a posture draws inward it is called “Lu” or rolling back. When a posture goes outward and forward it is call “Gee” or pressing. But even this manner of expression is incomplete. Because in any posture the hand method may transform into 8 different applications 8 x 8 = 64 different hand methods. The change of hand methods could be endless. Among them some are open and obvious and other are hidden and secret. The former can be seen and the latter are invisible to outward appearance.

Among the hand methods, which cannot be seen are sticking, adhering, joining and following. Also, there are “Peng” or ward off, “Lu” or roll back “Gee” or press, “An” or push down; “Lieh” or sudden response; “Jou” or elbow and “Kou” or shouldering.

The characteristics of Taijiquan include sticking, adhering, joining and following; its 4 basic hand methods of “Peng”, “Lu”, “Gee” and “An”, and its 4 auxiliary hand methods of “Tsai”, “Lieh”, “Jou” and “Kou”. These are the main forces of Taijiquan.

Then practicing Taijiquan the internal Qi flows. Opening and closing are performed like “drawing silk”. In applying these there is the hand method of “sticking”. Even if the force may break, the mind continues. Should the mind break, then the spirit continues. With regard to the methods of “joining and following”, when the opponent issues his power, I am soft and yielding. When the opponent neutralizes my force, I will follow him. This is the method called “Following”.

There are many responses which are not easily understood. There are no fixed applications in form. For instance, the posture of “Buddha’s warrior attendant Pounds the Mortar” has many different possible applications. The up raising fist could be an upper cut or pulling the opponent into an uppercut punch. The two hands hitting together could be punching the opponents wrist from above while holding below or striking the opponent’s arm from both sides. The upward arm movement can attach to the lower groin level or upward to the head. The hand descending could be hitting down on the forehead with the fore knuckles of the fist. As the saying states “a fixed method is no method at all”.

STANDING

When we are practicing Taijiquan we are really practicing the “stance keeping.” The “Wuji stance” practices standing in a fixed position, without stepping. Practicing the form we are still practicing “stance keeping” with moving steps. Push Hands is also a type of stance keeping. When practicing Push Hands we are practicing the hand methods with the upper body while practicing fixed stance — keeping with the lower body. Both upper and lower body are in a state of quiescence. When practicing the Taijiquan form both our upper body and our lower body are moving together. This may be called stance keeping with moving steps or Dynamic stance keeping with moving steps. There is also a type of quiescent stance keeping with moving and fixed steps.

We treat all these movements as practicing stance keeping, thus achieving greater results. In doing so we may achieve the flow of internal Qi within the body. Through this type of practice, one will understand that Taijiquan is an exercise that promotes the flow of internal Qi. The movement of the internal Qi combines with the outward manifestation of form. This we can call it a combination (union) of the internal and external. Otherwise, all you have are hollow postures or showing postures.

8 METHODS

In addition we should master the basic hand methods of Peng, Lu, Gee and An. We should be able to apply these methods flexibly and inter changeably. The force of Peng is upward. The force of Gee is outward. The outward force of “Gee” can be done with any hand position using the palms, fists or fingers. Backward movement is called Roll Back Or “Lu”. It can be performed with downward, sideward motion or even cross body motion using the forearms. Even the chest can be used to roll back force from side to side.

Downward Pushing is “An” and is accompanied by sinking in the “Kua” (inguinal crease between upper thigh and pelvis). Peng is upward movement and can be accomplished with any part of the body, whether wrists, palms or even elbows. These 4 basic methods can be done with any part of the body, not just with the hands or arms. Even the feet and legs can be used to apply these forces. The important part is the direction of force is clear the force is the same regardless of what part of the body is used. Only with this understanding can we actually practice Taijiquan according to Taijiquan theory. The directions of forces are always the same, only the form postures are different.

Of course there are all types of elbow attacks including forward, backward, to the side, up, down and outward. “Kou” is a type of striking, not just limited to the shoulder. “Kou” can be done striking with shoulder, chest, elbow or even the fist. It can be done with the knee, hip or even the head. Any part of the body can be used to strike with.

The 8 methods of using force should be used flexibly and interchangeable. We should clearly distinguish these methods when practicing the Taijiquan form. Another example might be “Lazily tying the Coat”. In this method, the lead right hand and stance draw backward. The lead hand drawing back could either be used as “Lu” or roll back or even as a strike. While drawing the body backward the rear hip and outward by could also be striking or pressing to the rear. When shifting forward the hand and knee could be striking or pressing forward. A Master expects his students to be able to learn more by analogy. If the Master shows 3 examples and the student cannot even understand one, then, of course, the Master will be upset. There is a saying that if the Master can show you one corner, the alert student can figure out the other three by himself.

HAND POSITIONS

There are lots of individual hand positions. There is the punch hand position with many variations. The fist can be horizontal with the palm facing down (Yang Fist Position) or facing up (Yin Fist Position). There is the vertical fist with the thumb facing upward, also called the Yin—Yang Fist. The fist can protrude the first finger fore knuckle or the middle finger fore knuckle for pin point targeting. There is another fist where all the fore knuckles are extended in progressive position. This fist, called the “padded fist”, is used for striking the ears or temple to either side of the opponent’s head.

There are many variations to the palm as well. There is the vertical (“Lee”) palm with the fingers pointing upward and the wrist down. The palm or palm outer edge can be used for striking. If the palm position faces upward it is called the “Yin” palm position and if it faces downward is called the “Yang” palm position.

There is a hand called the “Ba” hand position where only the forefinger and thumb are extended outward and away from each other. It is called the “Ba” hand because the thumb and forefinger position resembles the Chinese character for the number eight. If the palm faces upward it is called the “Yin” Ba hand position and if facing downward it is called the “Yang” Ba hand position.

Other palm positions include the corrugated or “tile palm” hand position. If the thumb and little finger close toward each other causing a closing of the palm crease in the “Lao Gung” or palm center it is called the Closing “tile” Palm position. There is also the snake palm and corrugated snake palm used when the palm is cupped and the fingers are pointed outward. If the fingers and hand are fully stretched and the fingers are pointed forward it is called the Snake Palm (as in the movement “White Snake Puts out its Tongue”).

Once again we cannot regard these various hand positions as rigid or fixed. They are interchangeable and flexible in application. A forward punch with a fist could change into a fore knuckle strike for penetration and pin point striking. It could also change into a finger extended snake (or spear) hand formation to reach a more distant target area or a palm strike for a closer target area. In short when practicing Chen style Taijiquan we must not be rigid in our applications. We must retain flexibility and rely on the guidance of Taijiquan theory and principles.

Lecture from 1988 transcript to Instructional 48 Form tape/dvd

Grand Master Chen Xiao-Wang Teaches Standing Mediation

by J. Justin Meehan, Esq. (c) 1996

U.S. Chen style practitioners last had the opportunity to study from”-the 19th generation Chen family lineage holder in 1988. At that time, Master Chen concentrated on teaching the “Yi lu” (the Chen family’s #1 form, from which all other T’ai Chi styles derive) and the Simplified 38 form created by Chen Xiao-Wang to introduce beginning students to the Chen style form and principles.

This past July and August of 1996, Master Ren Guang-Yi brought his master, Chen Xiao-Wang, back to the U.S. What a difference those eight years made. Grand Master Chen relocated to Australia and mastered the English language. In addition, he now felt comfortable teaching the inner dynamics of the Chen family style.

By way of introduction, Grand Master Chen said that a very simplified classification of the three major levels of development of Chen style T’ai Chi could be categorized as follows:

Level One: Learning the form, choreography, and body mechanics correctly. This could correspond to the “Yang” or external aspects of T’ai Chi development (which Grand Master Chen concentrated on in 1988).

Level Two: Learning to perform the form movements in a slow, continuous and smooth which exemplifies correct T’ai Chi principles and the correct flow of “Qi” internal energy throughout the body. This could be considered the “Yin” stage.

Level Three: Performing the movements with proper Qi flow and also with a correct understanding of martial intention and applications. Her both Yin and Yang aspects -ordinate and combine into a comprehensive whole or “T’ai Chi balance”.

In 1988, Master Chen focused on form and learning the entire form sequence. Many students overwhelmed with the quantity of movements to master. However, this Summer, Master Chen concentrated on the internal aspects of Chen form. He purposefully emphasized quality over quantity.

His teaching this Sumter began with emphasis on standing meditation instruction and then comprehensive and detailed analysis u of four basic “Ch’an Szu Chin” exercises. The emphasis was not just on doing the movement correctly, but on developing the awareness of proper Qi flow and the creation of a “Tan Tien center” as the cornerstone for all further development.

In 1988, St. Louis hosted Grand Master Chen Xiao-Wang for a week-long seminar. At that time, he discussed standing meditation and the basic Ch’an Szu Chin (C.S.C.) exercises. In the limited time (one week) available, however, we were only able to learn the external aspects of C.S.C. and how to do the form correctly. In 1996, Grand Master Chen discussed openly and completely the purposes of standing and C.S.C. and the internal energy (Qi) flow necessary to unite both outer body with inner Qi circulation.

To begin with, each of the four classes sessions began with at least 20 minutes of Standing Meditation (other known -Holding the Post” or “Wu Chi” standing). Master Chen explained the importance of utilizing standing meditation to create a fixed Tan Tien and “Qi center”. The posture’s position was slowly sculpted within an as we closed our eyes and were verbally guided by Master Chen’s calm, but precise instructions. He emphasized the importance of the standing posture being relaxed, natural, and comfortable. This allows the energy to flow naturally, to collect in the Tan Tien and then spread out from the Tan Tien center (three inches below the navel and midway from the front to the back) to every part of the body.

Posturally, he aligned the body from the side view by creating vertical alignment from the ear to the shoulder, to the hip, and to the ankle. One simple correcting exercise would be to hold a straight stick vertically and to measure one’s partner’s side view vertical alignment. He also pointed out a self-correcting practice to align the body ourselves by standing with back and head to the wall until our heads and backs were aligned.

His progressive instructions to us as we practiced the posture included:

- Raising,the top of the head upward

- “Listening behind you” (which has very interesting physiological and psychological effects on the overall meditation)

- “Balancing the mind’ (as in calming the mind, balancing the posture is not enough)

- Aligning properly from the ear to the ankle (as previously described)

- Relaxing the Tan Tien center

- Balancing the Qi within the body;

- Sinking the body and weight downward;

- Balancing the weight distribution;

- Allowing the Qi to descend downward to enter the Tan Tien center;

- Achieving quietness;

- Relaxing the spine (each vertebrae individually, from top to bottom);

- Relaxing he mind by “balancing the mind, balancing the weight, and balancing the Qi” within;

- Standing quietly (“like a mountain”);

- Slowly raising and riffling the arms in front of the chest to a comfortable position.

- Finding one o own best posture, based on ones own ability and using the criteria of adopting the posture which feels most balanced, most comfortable, and is the most conducive to the Qi being able to flow within.

There were additional instructions given, but, the above should suffice for.those who did not have the opportunity to attend. The primary purpose, besides quieting the mind, going within, and achieving the most aligned posture, was to create a “Tan Tien center”. From a purely external view point, this involved creating a focused and stable center of gravity. Master Chen’s specific instructions, however, were to locate and stabilize the .Tan Tien center. in such a way as to create a “Qi center” toward which all energy would flow toward, entering and accumulating within, and from which the Qi would then flow outward to support all movement. He stressed that although the variations of potential body movements was limitless, any changes in the body’s position through movement could never compromise the central position of the Tan Tien or Qi center within.

He personally led the entire group through these verbal instructions for standing posture and then went around to correct each seminar student personally. He was adamant about not becoming overly conscious of the role of the breath at this early stage and recommended only that each student just breathe naturally.

Chan Szu Chin Exercise of Master Feng Ziqiang

by Sifu Justin Meehan

Master Feng’s system of Chan Szu Chin exercises is derived from the Chen family style of Taiji, taught to him by Master Chen Fake in Beijing, China, and from his Xin Yi lio He Quan background with Master Hu Yao Zhen. Master Feng puts great emphasis on the practice of both Qigong and Chan Szu Chin exercises to improve Form, Function, Health, and Push Hands skills. Because of the necessary terseness of the Chinese language, I thought it might be interesting to examine a few of these exercises in greater depth. I apologize in advance to my teacher, Master Zhang Xue Xin, for any errors or mistakes which are the result of my misunderstandings alone.

Chan Szu Chin exercises are an excellent means of practicing Taiji principles of movement. For many of us, practicing the form alone is not the easiest way to improve our skills. In the form, we are often just finishing one movement, when we have to go on to a new and completely different movement in the form. Although there are repetitions, they are spaced away from each other and not practiced repetitively. This is where the Chan Szu Chin exercises come in. They allow us to practice basic body mechanics, which will form the basis for one or more movements contained in the form. They allow us to focus more carefully on the important principles of movement required in the Chen style.

Although Chan Szu Chin exercises are found exclusively in the Chen style, other styles often accomplish the same result by repeating individual movements. By way of example, both Yang Zhenduo and the late Fu Zhongwen advocated the repetition of individual basic movements from the Yang form as a way to improve performance and to develop internal power. In addition to Chan Szu Chin exercises, the Chen form has its own supplementary power training exercise, such as twisting the short stick (for Chin Na), shaking the long staff, and rolling the Heavy Jar (for developing waist power and body connection). Master Feng’s style includes training supplements as well.

- Side-to-Side neck turn

- Rolling the head around the neck

- Circling the shoulders (individually)

- Double shoulder circles

- Forward and backward double shoulder press

- single arm circle (left and right)

- Single under arm spiral and press

- Double alternating under arm spiral and press

- Double arm counter circles (Tying the Coat)

- Finger thrust and chop with waist turn.

- Two arms circle in, up, and out and then press down at the sides

- Two arms circle in, down, and out and then lift up at the sides

- Circle arms out and double finger thrust forward on each side

- Circle arms in and chest thrust out

- Double arm spirals under arms and thrusting out to sides (and reverse)

- Left upward and outward “Golden Cock” arm spiral

- Right upward and outward “Golden Cock” arm spiral

- Double elbow circles (forward and backward)

- Single elbow circles (left and right)

- Single wrist circling (outward and inward)

- Double wrist circling (outward and inward)

- Left and right spiral punching (in left then right bow stance)

- Circling the hip (a) sideways (hula hoop), (b) upward, and (c) downward

- Twisting the waist with double arm swing from side to side

- Circling the upper torso around the waist

- Circling each knee

- Circling both knees

- Circle and kick with each leg

- Turn the foot and leg in and out (left and right)

- Shaking the body

What I would like to do in this article is to go into a more complete description of three of Master Feng’s Chan Szu Chin exercises. This will give the practitioner a greater appreciation of the technical requirements of these exercises. Hopefully, the reader will even be able to practice these exercises on his or her own. They are certainly helpful regardless of style. Keep in mind that these are not just “range of motion” or “loosening up” type exercises. They will increase range of motion but in Taiji, no part of the body should move in isolation. “When one part moves, the whole body moves” is a good maxim to keep in mind. Beginners should emphasize integrated whole-body movement “led by the waist.” More advanced Chen-style practitioners should remember to keep “peng” alignment throughout and to circle each and every moveable body part in a coordinated fashion to increase “spiral” body power. I have chosen three of the easier exercises to focus on: Single Shoulder Circling (#3), double shoulder circles (#4), and Waist Turning (#24).

Exercise #3 Single Shoulder Circling

Purpose: The purpose of this exercise is to increase the range of motion in the shoulder and to open and close the “thoracic hinge,” which divides the chest and back along the center line (see August 1994 Tai Chi Magazine regarding the “Thoracic Hinge”). This will also aid in the ability to neutralize by rolling the shoulder and to develop the power of “kou” or shoulder smash.

1. Forward Shoulder Circle:

Stance: Stand with left foot forward about the natural distance of one step. The front foot faces forward with the rear foot turned out at a 90-degree angle. This stance is like a shortened front stance. As the shoulder rolls and circles, the weight will shift forward onto the front leg and then backward onto the rear leg. The knees are kept bent and the weight of the body is kept lowered. Do not let the body stand up out of its rooted position on either leg. Compress and expand the Kua to sink and rise (see 1994 Tai Chi Magazine regarding “Pumping the Kua”).

Body Movement: For the Single Shoulder Circle, there are two main variations: (1) circling upward and backward or (2) circling forward and downward. The lead shoulder is doing the circling and the rear shoulder remains back in a relatively stabilized position. The lead shoulder will be making a complete circle. After completing at least 9 repetitions with the left foot forward, change the stance and do at least 9 repetitions with the right foot forward. The important distinction between this exercise, as opposed to a simple flexibility or “range of (shoulder) motion” exercise, is that in Chan Szu Chin exercises the whole body is involved, not just the shoulder. The shoulder turning should be the result of shifting forward and backward in stance; raising and lowering the body; circling the “tantien/mingmen ball”; and opening and closing the chest and back at what could be called the “thoracic hinge.” This is not just an isolated shoulder movement. Try to involve the whole body to create the maximum shoulder circle.

2. Backward Shoulder Circle

This is the reverse of the forward shoulder circle. In this exercise, push backward from the front left leg to the rear right leg, raising slightly. The forward left shoulder will rise with the lifting body. The left shoulder and left side of the chest will open outward, opening the chest at the sternum. The body will continue to circle the shoulder backward and downward as the weight shifts and sinks downward on the right rear leg. The body will then bring the shoulder from underneath to forward as the body shifts from the rear leg to the forward left leg. Now the chest is closed or hollowed and the back is open or rounded. Do at least 9 repetitions on each side with the left foot forward first and then reverse the stance. Some important points to remember are to keep the rear shoulder backward. There is another Chan Szu Chin sub-exercise, which alternates shoulders, both rolling simultaneously, but this is not the exercise which I am describing. In this exercise, it is primarily the forward shoulder circling and not the rear shoulder or both shoulders circling together. By keeping the rear shoulder backward while circling the forward shoulder, we make it easier for the chest and back to open and close. This also helps to increase the range of motion of the lead shoulder. Another important point is to avoid the tendency to bend the torso forward and backward at the waist. Try to keep the torso vertical and upright throughout.

Just as the leg has a “Kua” (crease between upper thigh and front torso called the inguinal groove or crease) so also does the shoulder have a “Kua” (also called the “Shoulder Nest” by Denver based Chen-style instructor Liang Bai Ping) in the front of the body where the shoulder crease can open and close adjacent to the pectoral muscle. Try to maximize the opening and closing of the shoulder “Kua” and the “Thoracic Hinge.” Another benefit of this exercise is that it can massage and invigorate the heart and lung region and expand oxygen capacity.

Applications: As with all Taiji movements, there are numerous applications within the circularity of any movement. A description of any one application should not be considered exhaustive but merely illustrative. However, doing the movement without any understanding of application can also be limiting.

For the Backward Shoulder Roll, imagine or have someone push against the front of your shoulder. Instead of resisting the push to the lead shoulder, neutralize the push by rolling the shoulder upward and backwards and opening the chest, in order to neutralize the punch.

For the Forward Shoulder Roll circling up from behind and down the front, you can think of practicing “Kou” or a downward smash to the body of a close range opponent.

Other Exercises: After doing the left shoulder, change position and do the same exercise with the right shoulder. After doing the backward shoulder circle, try turning the shoulder in the opposite circle, creating the forward and downward single shoulder circle. Just reverse the instructions already described. One can also try the following exercise:

Exercise #4-Double Shoulder Rolls

Begin this exercise by standing in a forward-facing, Chen-style “horse” stance and circling both shoulders backwards. After that, circle both shoulders forward and inward simultaneously. The key is to raise and lower the stance while opening and closing the chest and back. Do not stand up all the way so as to straighten the legs or to lose the power potential of the hip joints or kua. Once again, do at least 9 repetitions forward and at least 9 repetitions backward.

Application: The Double Backward Shoulder Rolls could be used to disengage a two-handed forward push to both of your shoulders, and it forms the basis of an important two-person “Push Hands” exercise. This popular two-person exercise is shared by many different styles and masters, including my first (in 1967) Taiji instructor, Master William C.C. Chen.

Form: The ability to open and close the shoulder “kua” and to circle the shoulder is an important sub-movement to many movements in the original Chen form, Master Feng Zhiqiang’s simplified 24-movement Form, and his 48-modified Chen form. The Forward Shoulder circle can be seen as a closing movement preceding the White Crane Spreads Wings posture and can be used to strike the opponent’s ribs with your shoulders after deflecting his punch. The Backward Shoulder Circle is seen as the Double Arm Opening just before Movement #8 “Lifting Hands and Raising Leg” and before Movement #29 “Shake Both Feet.”

Exercise #24-“Horizontal Waist Turn”

(Side-to-Side Waist Turn)